This isn’t my usual thing, but something fascinating just happened and I’m in a rare position to offer a fast reaction to it.

For a few brief moments today, every hobbyist day-trader in the United States was convinced that a bomb had gone off in front of the Pentagon. Over the ensuing several minutes, stock values collapsed in response to algorithmically fed news tickers on trading platforms reacting to tweets.

The image is a fake; consensus has developed that it’s the result of a generative AI being prompted to generate an image of “an explosion at the pentagon.” It’s almost a certainty that this event (the hoax, not the explosion itself which did not happen) can and will be used as further evidence of the danger of deepfakes, of the ethical and epistemological hazards of generative AI. These are good arguments, fun to advance and timely to boot, but there’s nothing new here: what happened in the above image could have been accomplished by a particularly talented Photoshop user in 2005, or a talented airbrush artist in 1955. Image hoaxes are old traps, used primarily because they work; making this into a conversation about AI would, like most conversations about the harms of AI, mistake the instrument for the use.

I’m also only interested in the alleged connection to Russian actors insofar as it presents interesting ways of thinking about the present lukewarm superpower conflict as a war like Baudrillard’s Gulf War, as “a matter of war-processing in which the enemy only appears as a computerized target, just as sexual partners only appear as code names on the screen of Minitel Rose” (The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, 62). Fitting that Twitter, already like Minitel in that people use it to try to fuck, is the surface for this kind of information warfare. But our new cold war does not mean, or even necessitate, Russia (or anywhere else); the assailant could have easily been a different nation state, or a terrorist network, or some or other particularly devious trader who knew how news tickers on trading platforms got their news and knew when to time it to try to drop the value of SPY. It is tempting to say something like “the real cold war now is between real and artifice, between truth and lie, between those who believe in objective reality and those who reject it,” and draw battle lines between oneself and whoever one wants to position as a suitable enemy of reason. The problem with having a long memory is that I remember how many times the sides in that war flipped; the partisans take turns claiming to be on the side of “science” or “facts” and this motion from pole to pole is the latest engine of perpetual conflict. We must learn to think new thoughts, outside the warzone.

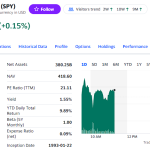

Let us advance a suggestion instead: the fake pentagon bombing and the circumstances around it – from the tweets, to the corrections, to the market collapse and near instant recovery – are art. They are perhaps the first art truly made in recognition of the idea, posited by Ulysse Carrière in Technically Man Dwells upon this Earth, that “a subject is not necessary for the production of art,” an art “beyond the subject, beyond authenticity, beyond lived experience” (44). Nothing about the art is represented in the image itself: that building does not look like the Pentagon, or even like a structurally possible building, and the explosion is almost painted where it sits on otherwise undamaged lawn. Nevertheless, this is “A Picture of an Explosion Near the Pentagon,” (artist unknown)and the way you view this art is either by witnessing frantic, conspiracy-minded tweets or by looking for the dip in the price of SPY, an ETF tied to the S&P 500:

The canvas is the stock market, or the Twitter algorithm, or the various systems that scrape the internet to detect news before it is made into news; the paint is mechanical artifice (to call this a use of artificial intelligence fits as poorly as any other use of that term; what exists that we call AI is a machine for producing artifices for later use) and timing. Nobody made the art; nobody had to. Stolen labor made the images that trained the algorithm that generated the initial image, yes, and exploited labor classified those images (and one shudders to think of what kinds of images one would have to sort through to build a model that can generate images of explosions in front of buildings), and knowledge workers in the imperial core developed the methods by which that data could be transformed into seemingly-novel images, but the image isn’t the art. The art is that dip, just before 10 AM eastern time; the art is the tweets inventing a whole faction of right-wing terrorists out of whole cloth (or retrofitting one that has already been concocted in a fascist bricolage) or situating the image in its target context of day trader “whales” who feed on information and derive sustenance from its novelty more than its relationship to the material world. Nobody’s inner truth is shown here, nobody is represented or will be seen in the encounter with it. The thing that gives substance to the art is the interaction between (false?) information and (true?) trading conditions.

When the art market is under siege, make market art.

🔥🔥🔥

Fuckin a